A Brief Schema of the Person

by John Tarvin

8.25.23

With the looming crisis of an election to establish a constitutional right to abortion in Ohio, the abortion debate is yet again thrust to the forefront of Catholic consciousness. By this point, many Catholics are seasoned veterans of this debate. While many have remained vigilant, some have grown jaded from the long struggle and others were lulled into a false sense of security following the Dobbs v. Jackson decision.

For me, going to the March for Life every year in high school was one of the things that motivated me to take my newfound faith seriously. That said, only a few years later, I too feel myself suffering from pro-life fatigue, but I cannot allow it to take hold, and neither should you. Now, more than ever, we are needed at the ramparts to do battle once again.

How do we combat this fatigue? I would posit that the bulk of it comes from the fact that many of us attempt to memorize arguments’ points and counterpoints without a deeper understanding of their philosophical underpinnings. In so doing, we risk coming into the debate with a different set of assumptions from our opponent, which makes communication even harder. This approach can work, but it is often leads to misunderstandings and leaves us unable to construct arguments ourselves. Being an effective witness to the Truth requires more than simply seeking to memorize a collection of true things. We need a philosophical approach to avoid sounding trite to those who do not already share our beliefs and creates the opportunity to establish a common foundation of truth upon which to build our case, instead of memorizing a selection of pithy comebacks.

The pursuit of this unifying Truth is ultimately only properly contextualized in theology. All knowledge that we observe in the world, regardless of its source, is ultimately rooted in the person of Jesus Christ, but the question still remains: how do we seek to share the truth with someone who does not know Jesus? We do this primarily through philosophy. We, as people seeking to evangelize others to adopt our perspective on this most central issue, should strive to build a bridge with our witness of love across which truth can cross, which is chiefly done through engaging people’s individual intellect at the place that other person is capable of grasping. To do this effectively, we need to use philosophy.

Today, many seem to be confused about the exact point at which human life begins and, as such, it has become a matter of debate. This confusion often results from thinkers approaching the question from the wrong frame of reference. Since modern times, people have tended to adopt some notion of “scientism,” the belief that the natural sciences can answer every question and account for all phenomena.

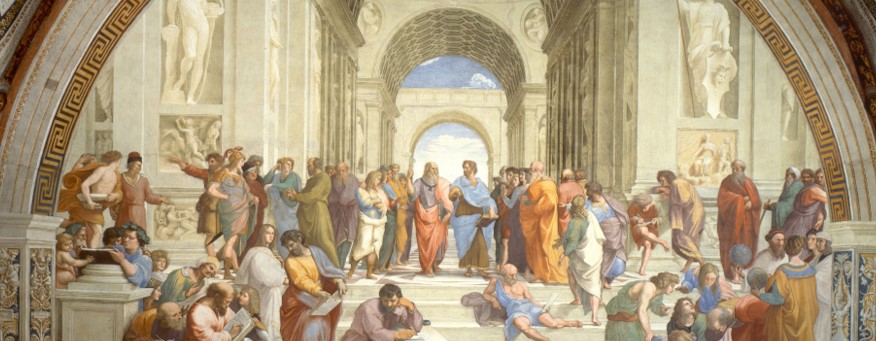

Scientism’s proponents ignore Immanuel Kant’s maxim that one cannot derive facts and values from purely sensory experience. Rather, an a priori framework is needed to sort sensory information into categories of thought, from which man can derive answers to questions of philosophy and morality. As one such question, the beginning of human life, cannot be determined simply from the facts about human development derived prima facie from modern science. They are ipso facto incapable of answering the question. Although science is a necessary part of the answer, a proper philosophy of nature that goes beyond the mere facts is needed, and who is better to turn to than Aristotle?

To lay out the parts of Aristotle’s philosophy relevant to the question of human life, some terms ought to be made clear, the most fundamental of which being substance. While most people have a notion of substance as something concrete, or tangible, according to Aristotle, a substance is a composite of both matter and form, which possesses a real, intrinsic unity. For example, a rock. A rock is something that can both shatter a window, and can be visualized in our mind’s eye: in other words, it has both tangible reality and conceptual unity, i.e., form and matter.

Matter is simply that out of which a thing is made, in other words, “what stuff it is.” Form is a little more complex. To describe form, Aristotle uses the Greek word, eidos, or the “look” of a thing. However, this “look” is not only what we see with our eyes, but also what we see with our minds, it is the “look according to reason.” Note well that a thing’s form also includes its specific actions or the functions it carries out according to its nature.

So, to sum it up, a substance is a real thing that exists in the world which has an intrinsic character or nature whereby it acts or functions, and each thing has its own nature and its own set of characteristic acts and functions.

Another way of looking at it is in terms of potentiality vs. actuality. Aristotle explains this in terms of first and second potentiality & first and second actuality. All matter possesses the property of potentiality and actuality in these different degrees according to the kind of matter referred to. That which is entirely potential with no actuality whatsoever, he calls prime matter; logically prime matter is not a thing, i.e., nothing. An example of first actuality and second potentiality is carbon; carbon is either potentially organic or inorganic. However, even that state of potentiality is unique to elemental carbon, that state of being either organic or inorganic itself is first actuality. Hence, first potentiality only applies to that which has the bare actuality of existence. Second actuality is simply the state of carbon as either organic or inorganic.

So, this “prime matter,” or that which is a precondition from which everything is made, is the only thing which can properly be said to have first potentiality. As soon as this prime matter is actualized into a particular kind of thing, it possesses second potentiality, which is identical to first actuality. Second potentiality is the matter constituting a thing, and first actuality is the form of a thing. When this thing possessing both second potentiality and first actuality is itself actualized through the particular action of its specific nature, such as water, which attains second actuality when it is frozen or boiled.

A thing that possesses first actuality is already the kind of thing to which the particular manifestations of a specific nature belong. For example, dogs are animals that can see the world, but a blind dog is still a dog. Being blind does not mean a dog ceases to be a dog; it just means that its power is limited by a defect in the operation of its nature. A thing’s nature is defined as an intrinsic cause or principle by which that thing acts or reacts, not by virtue of something outside itself, but of its own internal character.

All things have a nature, and those things that have a higher nature than others, which is only to say in a sense that they have more powers or functions proper to them than do other things. For example, water can be said to be higher than elemental oxygen or hydrogen because their combination produces an organized unity with an entirely different nature, capable of more than its constituent elements separated from the molecule of water.

Perhaps the most significant difference in the hierarchy of forms is that between living and non-living things. The difference is so vast that Aristotle created a new concept to explain that distinction—the idea of the soul. Put simply, a soul is the form, or first actuality, of a being which is capable of life. Like lower forms, souls have their own hierarchy of natures based on differences in the powers or activities proper to individual organisms. For Aristotle, plants, animals, and humans all have souls. Plants have the lowest, most basic soul since they possess only the basic nutritive powers necessary for life. Animals possess a higher soul due to their advanced sensitive and locomotive powers. Ultimately, human beings have the highest soul, since our nature is able to combine all of the aforementioned powers in addition to the power of rationality.

To Aristotle, the operation of nature is also intrinsically purposive, meaning that the functions of a thing’s nature are always directed toward the end, or telos, of that thing’s good. For example, when the sperm and egg of a human being meet under the right conditions, a zygote is formed, and, unless interrupted in a significant way, that zygote will develop into a mature human being. It never turns out to be something else, never a frog or a lobster. It always produces a human being, unless a defect, or deformity, or especially a deliberate act occurs that results in an interference with this process, which we rightly call mistakes. The mere fact that these mistakes occur show the very standard by which these processes are meant to happen, henceforth the end to which they are ultimately directed. All the operations of nature are laid out in these terms.

Given nature’s purposiveness and nature’s hierarchical structure with man at the top, one can bravely state on philosophical grounds that all of nature is intrinsically organized to bring about and sustain man in every necessary way, not by the constant action of an extrinsic agent, but through its own intrinsic organization. Theologically speaking, this is not so that man should domineer the nature under him, but rather steward it as a gift on behalf of the one who gave it to us.

Having thus articulated this basic philosophy of nature, we have the right frame of reference to answer the question that began this article: when does human life begin? Through Aristotle’s philosophy in union with what we know from modern science, human life, hence personhood, begins the moment when the process of human development begins to act intrinsically by the operation of a particular human nature. Modern embryology shows that this process begins at the moment of conception. Whether or not this process is later thrown off-track is irrelevant to the simple facts of the matter. Whatever its shape, the human zygote, human embryo, and human fetus are all, in the fullness of the term, a human person. At any stage of its development, the preborn human possesses the same nature as the postborn human. It is from this principle that they deserve the full protection of the law.