Kindling (and Rekindling) Ohio’s Faith

by Riley Kane

11.10.23

The tragedy of November 7, 2023, will be realized slowly as lives are destroyed over the years to come. Whether it is the children who will be destroyed literally, or their would-be mothers who, regardless of their repentance, will bear the physical and psychological scars of their decisions. The idea that this was a proper subject for an election shows how lost our society has become. The precipitous decline of our culture is the direct result of the collapse of the Church. We are all familiar with the statistics of decline, but those sterile numbers are made real by the Archdiocese’s ongoing and painful (but necessary) process of consolidating and closing excess parishes. As was recently opined in Crisis, “We Live Among Barbarians.” No one can credibly claim that we live in a Christian nation.

I have been gathering responses from the organizations and people who fought against the amendment. Two common themes emerge: heartbreak and resolve—the pained recognition that we have lost the culture, and a tremendous amount of work needs to be done.

Pondering all this, I find myself reflecting upon, and drawing inspiration from, the beginnings of Catholicism in Cincinnati.

The Church is ancient, but not here. It is likely that the first Mass ever said in the present territory of the Archdiocese was celebrated in 1749 at the mouth of the Little Miami River before a party of French explorers.

In 1784, the Diocese of Baltimore, the first in the United States, was established with John Carroll its Bishop. Until 1808, it covered the entire country. Ohio Catholics were served sporadically, if ever, by itinerant priests. Early settlers went years without the Sacraments.

One settler decided to do something about it. Jacob Dittoe, a German Ohio farmer, wrote letters begging Bishop Carroll to send a priest and proposing that he purchase land for a church. Unfortunately, the Bishop could not afford the land and had too few priests to spare a permanent appointment for Ohio. However, with Dittoe’s letters in mind, the Bishop suggested to Fr. Edward Fenwick, a Dominican friar visiting from Bardstown, Kentucky, that he should return though Southern Ohio.

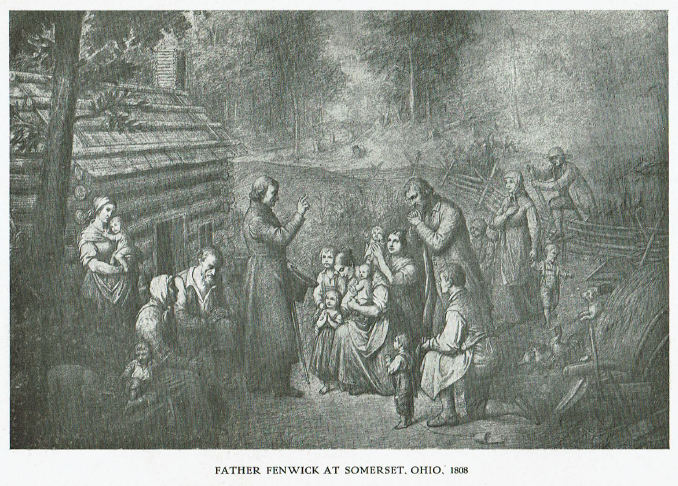

Fr. Fenwick found the Dittoe farm by the sound of axes striking the trees of the forest. The Dittoes welcomed Fr. Fenwick as “an angel sent from Heaven” and summoned two nearby families, they had not seen a priest for years.

This began Fr. Fenwick’s mission to the people of Ohio. While his obligations to the Dominicans in Kentucky meant that he could not devote himself fully to Ohio, he would visit when possible, continued to correspond with the Catholics of the region, and appealed to his superiors for additional support. Records suggest that, in the early years, Fenwick visited Ohio no more than once per year—but he tethered its people to Christ.

In 1808, the Church erected four new American sees, among them the Diocese of Bardstown, which incorporated all Kentucky, Ohio, and Michigan. In 1810, hearing about the appointment of Bardstown’s new bishop, Dittoe wrote Bishop Carrol asking that he encourage the new bishop to travel via Southern Ohio, as “there are some young Catholics in this place that do wish to join in marriage and are waiting upon that head of this coming, as it is a point of some importance; and should he not come, we will thank you to write us whether they will be allowed to be joined by an esquire, who is also a Roman Catholic, or not, as quick as possible.”

Such was the state of the Catholic religion in Ohio.

As the Diocese of Bardstown began to attract and consecrate more priests, Fenwick was freed to devote himself to Ohio. In December 1817, the newly-consecrated Fr. Young joined Fenwick. Now two, their work remained restless. Fr. Fenwick wrote that between 1817 and 1818 “I baptized in different parts of the Ohio State 162 persons both young and old whose names and sponsors cannot now be recollected, as I was then an Itinerant missioner—and such persons were generally discovered and brought to me accidentally—[Fr.] Young during his journey to Maryland and back to Ohio in this year of 1818, baptized about 30 in a similar manner.”

The Dittoes lived in the central portion of Southern Ohio, toward Lancaster and Chillicothe. Catholics were present in Cincinnati since some of its earliest days, but were few in number and far outnumbered by Protestants. However, contrary to rumor, it was paucity, not persecution, that most hindered our forebearers. The first attempt to build a church came in 1811, after Jacob Fowble’s wife, Margaret, died without last rights and had her funeral presided over by a Methodist bishop (no Catholic priest was present in the region). Sadly, this effort failed, as did two others in 1817 and 1818. It was not until 1819 that there were enough Catholics to successfully fund the purchase of land and construction of a wood-frame church—and they still had no priest.

On Easter Sunday, 1819, the first Mass was first said in Cincinnati’s first Catholic Church, Christ Church (which no longer stands). By the end of the year, the Bishop Flaget of Bardstown had written the Pope urging the erection of a new diocese in Cincinnati.

In 1821, the Diocese of Cincinnati was established, covering all of Ohio and Michigan, with Fenwick as Bishop. His appointment brought the opportunity for more resources, but now-Bishop Fenwick continued to minister directly to the people of his Diocese as he had done before. His congregation was largely made up of poor German and Irish immigrants, his Sunday collections regularly amounted to no more than a few dollars. Fenwick won converts and reverts. For instance, he “nearly ruined” Cincinnati’s Lutheran church by returning thirty-three wayward Catholic German families to the fold.

Fenwick’s episcopacy was dominated by industry. He traveled continually, crisscrossing Ohio and visiting Michigan to minister to his people. Fenwick traveled to Europe seeking financial support, which Pope Leo XII answered in the form of cash and “a trunk filled with ecclesiastical articles.” Bishop Fenwick arranged public lectures on the Faith, established the Catholic Telegraph, started the first seminary west of the Appalachians, and founded the Athenaeum. The Diocese was poor, indebted, and stretched thin—but was growing. Bishop Fenwick died in 1833 while traveling in Northern Ohio.

He had once been the sole missionary in the state. At his death, it held 16 churches and 7000 Catholics served by 14 priests.

Pope Gregory XVI appointed John Baptist Purcell the second Bishop of Cincinnati in 1833. He arrived to a city with 30,000 inhabitants and a single church. He too lived close to his flock and traveled extensively across his Diocese, which began to experience rapid growth.

Purcell was, however, also a scholar and engaged in a series of public debates with a prominent Baptist minister, Campbell, over two weeks in January 1837. Purcell smashed his rival. The newspapers attested to this fact. The Republican said it best: Campbell “retired from the contest pretty much after the manner of the sorry knight of La Mancha from his assault upon the windmill, crippled and discomfited.” Purcell would engage in other public theological debates, one with the Congregationalist Minister Vickers in 1868 and another with Reverend Mayo on religious instruction is schools—adding further victories in public discourse.

Bishop Purcell also inherited a heavily indebted Diocese and made numerous tours to Europe, seeking financial support. His tours were a success—he was able to stabilize the Diocese’s finances and fund the construction of St. Peter’s Cathedral (particularly with donations from France and Vienna). The Cathedral’s cornerstone was laid in 1841. In 1851, upon its elevation, Purcell became the first Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. By the time of his death in 1883, Ohio had grown to hold 500 churches with 500,000 Catholics served by 480 priests. He bequeathed a thriving Church to his successor, Archbishop Elder.

We find ourselves in a position not dissimilar to Bishop Fenwick or Bishop Purcell (at the start of his episcopate). Both were charged with the conversion of Ohio. Fenwick began alone. Purcell started with little. Ohio’s population was mostly Protestant. The few Catholics in the state were isolated, widely dispersed, and many had not been to Mass in years. Both Bishops were reliant on what little resources their flock could offer and had to beg for the rest.

We too are few, scattered, outnumbered, lacking resources, and charged with the conversion of Ohio.

As we mourn this loss and chart the path forward, we should look to the example of Bishop Fenwick and Archbishop Purcell. While our challenges are not precisely the same, the principle underlying their success is:

Both uncompromisingly sought first the Kingdom of God. Fenwick did not despair during his years as the lone itinerant priest for Ohio. Purcell did not shy away from public controversy on matters of Faith. Neither shrunk from the challenge of serving a vast territory. Neither despaired at the financial cost of their mission. Neither would have dreamed of toning down the Truth to attempt to court the superficial support of non-Catholics. Unconcerned with comfort, leisure, wealth, or worldly respect, they told the Truth and won souls for Christ.

As they built, we must rebuild.

The historical information in this article, and the cover image are drawn from the History of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati 1821-1921 by Rev. John Lamot, published 1921.